I have recently started the 2023 redesign for Antares Programming. The old design is getting old, and the file organization is starting to get hard to deal with. Plus, theming with both light and dark color schemes are getting confusing, and since I plan to open a YouTube channel for it next year, I want my new videos to appear on the website’s frontpage, so the redesign will also have to deal with that.

I have been working professionally as a software developer for almost 4 years now, and not once have I ever touched ReactJS, Vue, Angular, Svelte, and the like, which makes me wonder how I even made it in the industry. To be fair, most of my work involved backend projects even if I’m a frontend person myself. But all of my projects in the past have not been enough to warrant me reaching for JS frontend libraries.

For example, for Antares Programming, I have always used either Liquid or Nunjucks for templating and UI, eliminating the need for JS frameworks. And server-side rendered webpages have historically been faster than ones rendered on the client side. I use JavaScript for components, of course, but only sparsely to make certain components interactive.

Benefits of frontend frameworks.

Of course, there is no doubt JS frameworks have their benefits. They are popular after all, which must entail that they give something of value. And there are definitely projects where choosing vanilla over frontend frameworks does more harm than good, especially when a web app is more on the interactive side.

For example, some web apps benefit from data binding. This is when a UI component is tied to a data store or variable, and both of them update each other. For example, a form input can be data-bound to an object property, and whenever the user types in their data into the form input, the object property updates accordingly. In a two-way data binding, the form input’s contents are also updated to reflect the object property’s value when it is changed by the database or some other process. This is quite challenging to do in vanilla JavaScript, and sometimes you might as well just build your own data binding framework.

Reactivity also follows when you have data binding. You have to have an effective way of propagating changes. This is especially important when an object is data-bound to multiple UI components. Frontend frameworks do this for you, but if you choose the vanilla way, the closest you can do is to use events and observer objects that watch your object and dispatch events to UI components whenever their values change.

Disadvantages of frontend frameworks.

All benefits come with a cost. And for frontend frameworks, these costs come in the form of performance, SEO, file size, debugging, styling, and updates.

The most obvious one is performance. Frontend frameworks like ReactJS, Vue, and Angular cater to as wide an audience as possible. Therefore, they want to address as many developer pain points as possible. But the reality is, in most projects, not all of these pain points are present. This means that many projects take in solutions to problems they don’t even have. For example, I have seen learning developers who use ReactJS for their portfolios and blogs. And I get it, they want to get employed and they want to show their proficiency in this technology. But remember that ReactJS provides a lot of functionality that these kinds of websites don’t need. Portfolios and blogs are more content-based than interactive, so things like the virtual DOM just add to the webpage’s bundle size when the actual DOM just needs to be updated just once, namely, when the page first loads.

Also, some websites are empty HTML documents until the framework renders the entire page. Compare that to “old-school” server-side-rendered webpages that sends a complete HTML document that the browser can load and display as soon as it receives it.

Client-side rendering is also bad for SEO. Search engine crawlers previously didn’t try to run JavaScript when they crawled websites, which meant that if your website is heavily content-based, a lot of your content wouldn’t appear on search results. This is okay, I guess, if your website offers interactive utilities, like maybe photo, video, or audio editing, then maybe your frontpage is the only one that needs to be rendered server-side. But this is bad for many e-commerce sites that need to have their products appear on search results for people searching for things to buy. There are solutions to this, of course, like server-side rendering, but then again, it would just be like when we used to do web development with PHP.

Styling is also a pain point in frameworks. CSS is a powerful language. But with frameworks, its powerful systems for cascade, inheritance, and specificity are nullified because everything are styled on a component level. This is why things like CSS-in-JS are a thing, because styling is hard to manage in the context of JS frameworks. CSS is growing more and more powerful as the years go by, and it’s a shame that we are doing everything in JavaScript.

Building with vanilla.

Noam Rosenthal’s article, the two-part series What Web Frameworks Solve gave valuable insights as to how to build components without JavaScript frameworks. I like this solution more because it makes me use HTML, CSS, and JavaScript to their fullest potential.

Sending forms in just vanilla, for example, is much easier than some people would think. Nowadays, we want forms to be sent in the background, so we use the AJAX technique for that. By using

the document.forms property, you can access all of your form’s values without tediously using document.getElementById or document.querySelector.

<form name="form-newsletter" method="POST" action="/api/v1/submissions/newsletter">

<label for="full-name">Name</label>

<input type="text" name="full-name" id="full-name">

<label for="email">Email</label>

<input type="email" name="email" id="email">

<button>Submit</button>

<output name="form-message"></output>

</form>

In this snippet, we gave the form a name form-newsletter. We can then use that name to access the form’s values via document.forms later on. Notice that we also

gave our input and output elements a name attribute. Do not confuse this with the id attribute, which we put in there so we can attach the

label elements to the form inputs. The name attribute is what we’ll use to access the values.

const frmNewsletter = document.forms['form-newsletter']

frmNewsletter.addEventListener('submit', e => {

e.preventDefault() // so it doesn't refresh the page on submit.

const fullname = frmNewsletter.elements['full-name'].value

const email = frmNewsletter.elements['email'].value

const output = frmNewsletter.elements['form-message']

fetch('/api/v1/newsletter', {

method: 'POST',

headers: { 'Content-Type': 'application/json' },

body: JSON.stringify({

'full-name': fullname,

'email': email

})

})

.then(response => response.json())

.then(data => output.message = 'Form submitted successfully.')

.catch(err => {

output.value = 'Something went wrong. Check logs for details.'

console.error(err)

})

})

In this vanilla JS code, we have easily accessed the form inputs using the document.forms property. We then used fetch() to submit it to the server. Finally, we

used output to display the form submit’s result to the user. What’s good about using output is that it is by default aria-live in most browsers, which

means that whenever its contents are updated, assistive technologies like screen readers will announce it to the user, thereby alerting them to the result of the form submission.

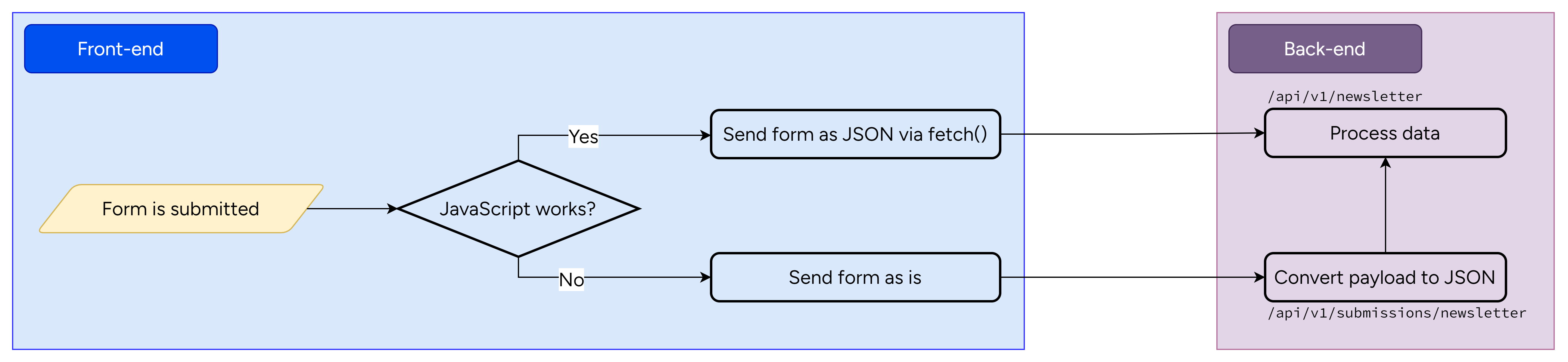

And look at our form’s attributes, specifically the action attribute. This means that by default, without JavaScript, the form will submit to that URL in the

action attribute. That makes our form progressively enhanced and we can now expect it to work on more browsers and even when our JS code fails for some reason. If, for example,

your API only accepts JSON payloads since that is what we gave fetch(), your form’s action attribute could just point to a different endpoint that takes the form

submission, convert it into a JSON payload, and send it to the actual API endpoint that will process the data.

Conclusion.

HTML, CSS, and JavaScript are all powerful on their own. In reality, frameworks are just there to make our jobs easier for us, and make everything abstracted and less verbose. But considering the trade-offs frameworks have, we must first look out and think if it’s really worth it.

The Antares Programming redesign is almost complete. I’m estimating around 80% of the site is complete at the time of writing. And right now, my front-end JS is sitting at around 4.68kb minified but not yet optimized, so every functionality across all pages are bundled within one JS file. I expect that to be smaller if I separate them across multiple bundles. And that’s a testament to the fact that vanilla JS can be made more performant than frameworks. Why not give it a try in your next project? It can be a fun challenge and a rewarding experience.